Sally Ottoson’s Pacific Star Winery isn’t in Napa, a region still recovering from losses from the summer’s earthquake. But along with “Where’s the bathroom?” and “Where do you get your grapes?” tasting room visitors at the Mendocino County winery want to know: “Where’s the fault?”

Answer: They’re standing right on top of it, and they’ll taste a wine in honor of the Pacific Star fault’s discovery, aptly named “It’s My Fault.”

“When customers ask for the wine, they don’t say “I would like a bottle of ‘It’s My Fault,” said Robert Zimmer, Ottoson’s friend, colleague, and tasting room employee. “They ask for a bottle of “It’s Not My Fault.”

(Even I, in an e-mail to the winery, said I wanted more information on “It’s Not My Fault”).

“It’s human nature to decline responsibility for many things,” Zimmer said.

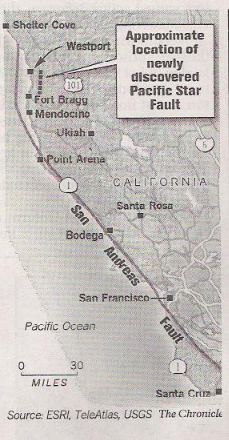

Zimmer takes full responsibility for naming the blend, – after all, he was partly responsibility for helping find the fault. A student of geology, Zimmer and many in the community had heard grumblings about the a fault running under the ocean-bluff bordered winery as far back as 2003. A month before Stanford University geologist Dr. Dorothy Merritts visited the winery 12 miles north of Fort Bragg, Ottoson and Zimmer had suspected the fault lay in a nearby cove. So when Merritts arrived , Zimmer was able to take her right to it.

Merritts revealed the Pacific Star fault officially at the 100th Anniversary Conference commemorating The Great Earthquake of 1906, held in San Francisco in April 2006 –same year “It’s My Fault” was first blended. So as Napa vintners now clamor for names to commemorate the 6.0 tremblor that shook the grapes making up the 2014 vintage and sent cellar barrels crashing to tasting room floors, this fall “It’s My Fault” is in its 8th release.

Like the fault up until its discovery, “It’s My Fault” remains somewhat of a mystery.

“She doesn’t even tell us what’s in “It’s My Fault,” said a tasting room employee on a visit to Pacific Star during a recent visit. “We call it Sally’s Secret Sauce.”

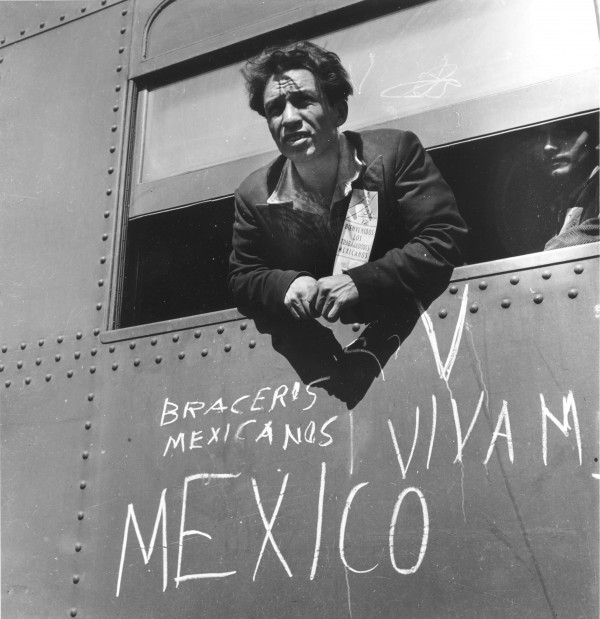

Sally, also the winemaker, uses grapes left over from some of Pacific Star’s best-selling single varietals, including Charbonno, Carignane, Zinfandel, and Petite Syrah – grapes that were “usually planted by someone’s grandfather many years ago,” Ottoson said. So a $15 a bottle of “It’s My Fault,” is made up of the same grapes that go into $28 bottle single varietals.

Ottoson says the Napa quake, which some believe connects to the San Andreas Fault, didn’t change any of her storage and production practices.

“We’re inspected by County Hazardous Materials storage,” said Ottoson. “We don’t have any…but they make sure everything is secured.”

###